Review: Nina Bohlen

by Alicia Faxon, Art New England, 2012

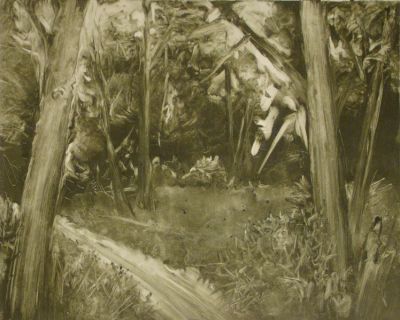

“Whose woods these are I think I know….” With these words, the poet Robert Frost might have been writing about the representations by Nina Bohlen on view at the Danforth Museum. In monotypes made in 2010 and 2011, the artist captures the fierce beauty of the woods surrounding her cabin in Lubec, Maine, the farthest point of land east on the coast of the Atlantic Ocean.

In Bohlen’s monotypes, each of the trees or animals she depicts are highly individualized, never generic. They are expressive portraits that evoke moods, temperaments, and relationships. With fine draftsmanship Bohlen has staked out a territory of her own in the stark presence of her familiar woods.

The expressiveness of Bohlen’s view is not surprising. She was a member of the Boston Expressionist group, whose work was exhibited at the Danforth Museum through February 2012. Although this group is usually identified by its legendary male members, including Hyman Bloom, David Aronson, Jack Levine, and others, little notice has been taken of the women who belonged to the movement. Nina Bohlen was one of them, as were Cleo Lambrides Webster, Esther Geller, Mariana Pineda, Barbara Swan, Marie Cosindas, and Lois Tarlow. Bohlen met Hyman Bloom when she was a student at Radcliffe College and studied painting and drawing with him at the Fogg Museum of Art and as a private student. “He was a wonderful teacher,” Bohlen recalled, “the best I ever had.” He taught his students to compose not directly, or immediately from nature, but from the memory and the imagination spurred by that encounter.

Bloom’s approach is evident in Bohlen’s monotypes of the mature forest in Lubec, Maine (named for Lübeck, Germany). In works such as one of leaning trees, trunks seem to be talking together. In others, like the one with a newly cut woodpile in the foreground, the artist contrasts the pile of bare wood with the forest of standing trees behind it. Her technique reveals juxtapositions of light and dark, rough and smooth textures, generalized setting, and individualized detail. A brilliant and incisive draftsmanship is evident. This same ability informs the sensitivity rendered in representing a deer’s head with precision.

Bohlen creates her monotype palette on site, with oil paint thinned with linseed oil to give the pigment body. Employing a white plastic support she works from dark to light, often using her thumb to create form and texture, then running the image through a press onto white paper. The technique is demanding in its exactitude and unpredictability, until the final image is printed as a one-of-a-kind monotype. Taken together, in these images viewers may feel they are walking through the woods with the artist, seeing sunlight dapple glades or barely touching the trunks of the trees.

The somber palette of current works is an interesting contrast to Bohlen’s monotypes based on puppets from Thailand, Indonesia, Bhutan and China given to the artist by her brother. Unlike the dark solitude of the trees, whose woods are devoid of human occupation or intimations of their presence, these earlier representations are very colorful and suggest a peopled stage. Bohlen’s monotypes have been shown at the Summers Gallery in New York, in Georgetown, Maine, and in three exhibitions at the Boston Public Library, with this the first showing of the forest monotypes.

One of the interesting aspects of Bohlen’s monotypes of the forest is their contrast with representations of trees by other members of the Boston Expressionist group such as those by Hyman Bloom or Cleo Lambrides Webster. Here the format is vertical and large, with frenzied branches in intricate weavings and an overpowering sense of turmoil. Bohlen’s monotypes are rendered in horizontal format and are serene, grounded in the earth. Their idiosyncratic expressiveness possibly mirrors the personality of the artist herself. There is a strong sense of solitude and quiet. “I know every one of these trees,” the artist said, and in one sense these monotypes are portraits of the woods in Lubec.

Bohlen also works in oil and in drawings in charcoal and sepia, but loves the challenge of the monotype process and the surprise of its final form. Since each monotype is an adventure into the unknown, not all results are successful. Hers is also a very physical process, using fingers and wiping rags, and it must be accomplished in a short space of time before the pigments dry.

In showing Bohlen’s monotypes, the Danforth Museum is following its tradition of exhibiting the work of the Boston Expressionists and also works of women artists. Under the directorship of Katherine French, there have been exhibitions of two of its main artists, Hyman Bloom and David Aronson. The latest exhibition in 2011–2012, The Expressive Eye, includes not only artists of the original group but also several contemporary artists influenced by the group or by an expressionist vision in general. Among those artists exhibited currently at the Danforth is a strong representation of women, from Elizabeth Awalt to Maxine Yalowitz-Blankenship. From this prelude Nina Bohlen’s monotypes stand out in their individuality, their evocative and sensitive nature.